Nella Larsen’s novel, Passing, revolves around the lives of two biracial women who predominantly construct their identities through performance, enabling them to pass as White. Larsen’s narrative implies that racial, gender, and sexual identities are not solely inherent but also heavily reliant on performance. The novel delves into the exploration of these identities in a world where passing is feasible, challenging the fundamental nature of these concepts and their intersections. It raises questions about how identity influences individuals’ experiences and how individuals, in turn, shape their identities.

Irene places significant emphasis on the notion of “uplifting the race” and actively acknowledges and explores her Black identity. However, in doing so, she overlooks the fact that her identity is inherently a mix of Black and White due to societal pressure that forces her to choose and perform within specific racial labels. Conversely, Irene criticizes Clare for opting to pass as White and enjoy the privileges associated with that identity in America. At the same time, Irene inconsistently engages with her own Black identity, selectively embracing it when it aligns with her needs or desires. Clare’s obsession with passing as a white woman devolves into a desperate longing for Irene’s carefully sustained Black identity. When it comes to expressing their racial identities, Clare and Irene are on opposite ends of the ideological spectrum. Unfortunately, these acts unintentionally promote the socially imposed assumption that biracial people must choose one part of their history to perform instead of embracing and expressing their biracial identity.

However, the assumption that multiracial people are born with conflicted or contradictory identities is fundamentally flawed. There is no logical reason to believe that such identities are fundamentally adversarial. By requiring multiracial people to choose a single racial identity to perform, society compels them to ignore an important component of their identity. As a result, they are frequently alienated from both racial communities, as their multiracial identity is often rejected or devalued by American culture.

“She was caught between two allegiances, different, yet the same. Herself. Her race. Race!The thing that bound and suffocated her. Whatever steps she took, or if she took none at all, something would be crushed. A person, or the race. Clare, herself, or the race.”

Larsons sentence structure is quite deliberate here and you can see the textual ambiguity by physically separating herself and her race at the beginning of the passage, Larson implies a separation between the two concepts as well. She later uses herself and the race in the same sentence but by adding Clare into the mix, Larson suggests that Claire is both separate from Irene’s race and represents 1/2 of Irene’s identity which is an adjuring identity crisis for Irene. The real doubleness Larson describes in the novel is the double Jeopardy implicit in being a black female and a white male hegemonic society, as the term passing is broad, and can refer to any form of pretense or disguise, that results in a loss or surrender of, or a failure to satisfy a desire for identity or sexual.

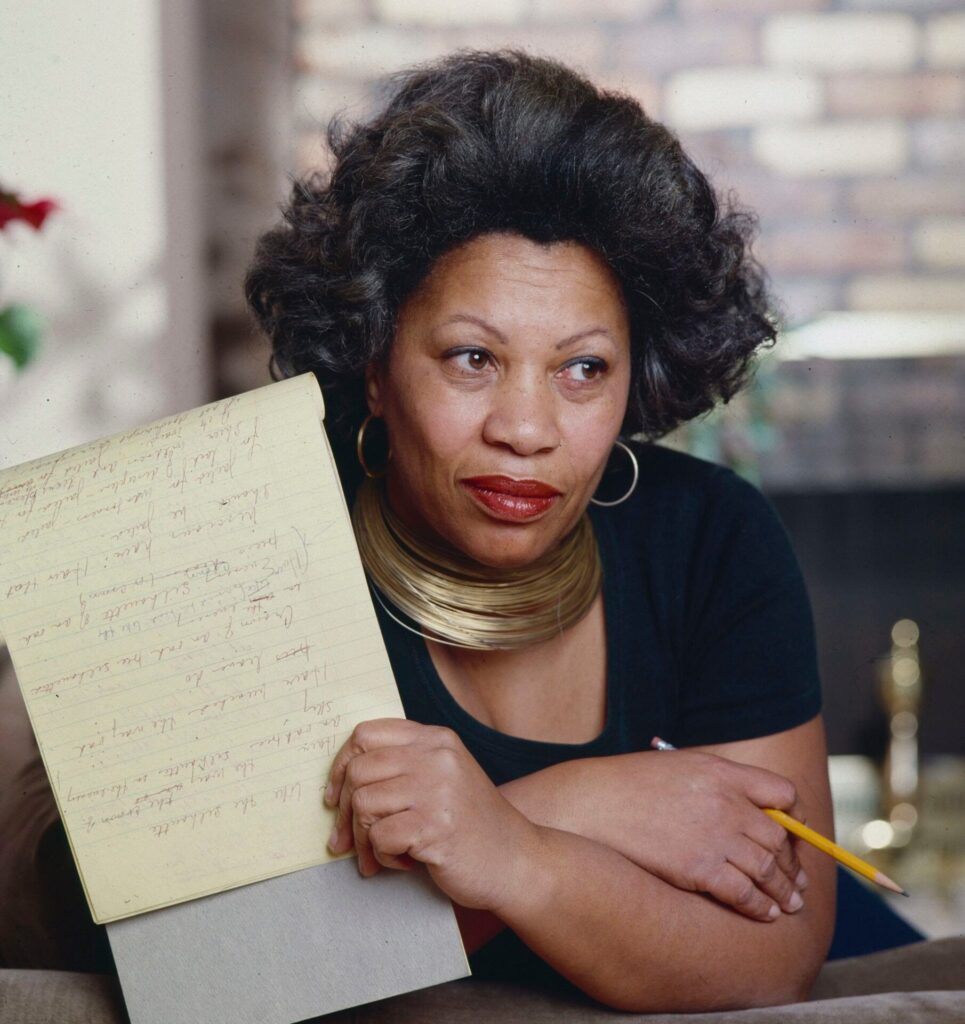

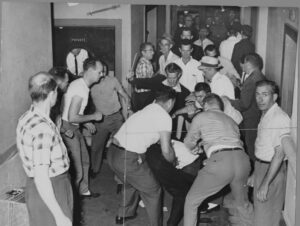

In the video below, a quote that caught my attention was at 3:24 when the elderly man states, “There will come a time where whites won’t accept you and negroes won’t accept you, I said I’ll wait it out”. This further shows the identity crisis once can face like Irene and Clare who are on the opposite sides of this spectrum. This video also shows a family who honors and respects their racial identity that was passed on to them and there is no confusion for them which is a contrast from Irene and Clare.